A Peek Into Crisis Policymaking

The

Great Recession of 2008 and the following sovereign debt crisis in Europe have

radically altered the response that government agencies adopt against financial

crises.

Great Recession of 2008 and the following sovereign debt crisis in Europe have

radically altered the response that government agencies adopt against financial

crises.

The

primary responsibility to combat a financial crisis lies with the central bank.

A central bank monitors the general economic health of a nation and is usually

mandated to maintain stable prices and employment level. They also undertake

the surveillance of—most of—the financial sector.

primary responsibility to combat a financial crisis lies with the central bank.

A central bank monitors the general economic health of a nation and is usually

mandated to maintain stable prices and employment level. They also undertake

the surveillance of—most of—the financial sector.

It

is important to know that there are only a finite number of tools by which a

central bank may fulfil its above mentioned duties. And, in the pre-crisis era

those tools were commonly two: Policy rates (Basically, interest rates that a

central bank sets) and word of mouth. Central banks would lower policy rates

when the economy fell into a recession, thereby dropping all market rates of

interest, boosting lending and thus the economic activity. They would also

announce to all the players in the financial arena the thinking behind lowering

policy rates and the goals the policy move seeks to achieve, thus guiding the

economy towards that goal.

is important to know that there are only a finite number of tools by which a

central bank may fulfil its above mentioned duties. And, in the pre-crisis era

those tools were commonly two: Policy rates (Basically, interest rates that a

central bank sets) and word of mouth. Central banks would lower policy rates

when the economy fell into a recession, thereby dropping all market rates of

interest, boosting lending and thus the economic activity. They would also

announce to all the players in the financial arena the thinking behind lowering

policy rates and the goals the policy move seeks to achieve, thus guiding the

economy towards that goal.

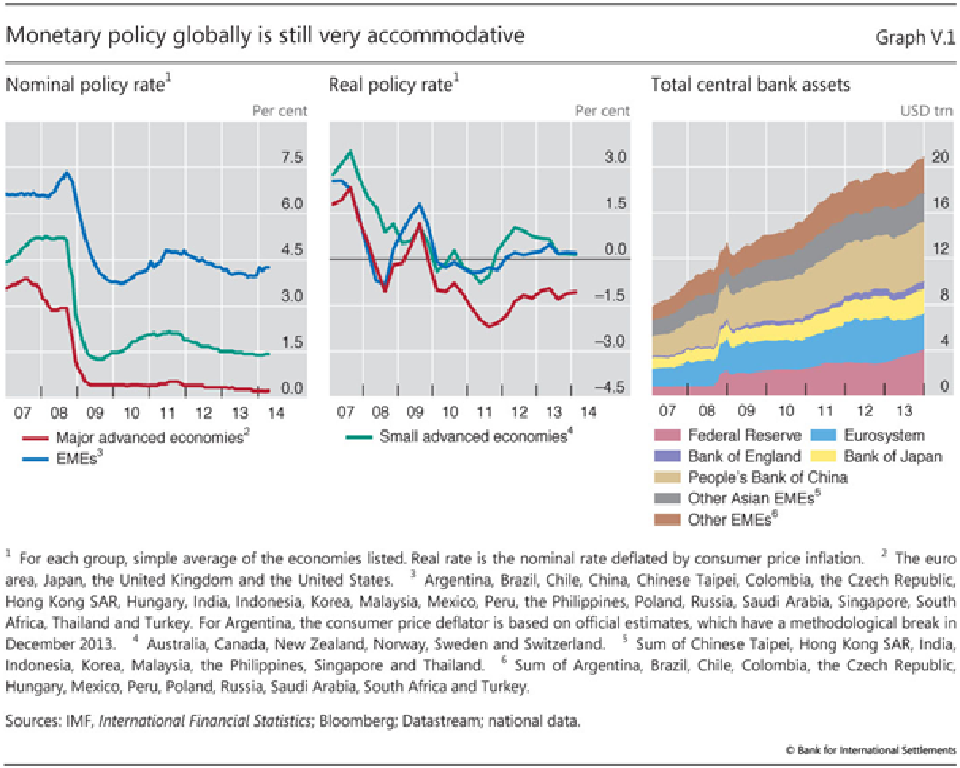

When

crisis struck in 2008, central banks—mainly the Federal Reserve, the European

Central Bank and the Bank of England—very naturally started lowering their

policy rates. Over time, they continued to lower rates to near zero

levels—while reassuring the markets via their press offices that the rates will

remain at ultra-low levels for an extended period—to keep the economic activity

afloat. This policy was dubbed ZIRP: Zero Interest Rate Policy.

crisis struck in 2008, central banks—mainly the Federal Reserve, the European

Central Bank and the Bank of England—very naturally started lowering their

policy rates. Over time, they continued to lower rates to near zero

levels—while reassuring the markets via their press offices that the rates will

remain at ultra-low levels for an extended period—to keep the economic activity

afloat. This policy was dubbed ZIRP: Zero Interest Rate Policy.

But

with the passage of time, ZIRP proved to be ineffective: Unfortunately,

interest rates could not be lowered below zero [1] and all the reassurances by

central banks failed to inspire confidence in the economy. This meant that the

conventional tools at the disposal of central banks were exhausted—with no

apparent improvement in the health of the economy.

with the passage of time, ZIRP proved to be ineffective: Unfortunately,

interest rates could not be lowered below zero [1] and all the reassurances by

central banks failed to inspire confidence in the economy. This meant that the

conventional tools at the disposal of central banks were exhausted—with no

apparent improvement in the health of the economy.

With

the situation deteriorating, central banks adopted bold policies that were

never before considered, and some of them were even taboo amongst central

bankers. The flagship of these policies was dubbed ‘Quantitative Easing’ or ‘QE’.

Under QE, central banks directly intervened in the markets to purchase securities—which

were primarily government bonds—by creating new money to fund these purchases.

This move appeared similar to ‘monetizing of government debt’ which had

resulted in hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic and Zimbabwe [2]. Under various

QE programmes, central banks infused an unprecedented amount of liquidity into

the system which lead their assets to soar—to levels north of USD 20 trillion!

the situation deteriorating, central banks adopted bold policies that were

never before considered, and some of them were even taboo amongst central

bankers. The flagship of these policies was dubbed ‘Quantitative Easing’ or ‘QE’.

Under QE, central banks directly intervened in the markets to purchase securities—which

were primarily government bonds—by creating new money to fund these purchases.

This move appeared similar to ‘monetizing of government debt’ which had

resulted in hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic and Zimbabwe [2]. Under various

QE programmes, central banks infused an unprecedented amount of liquidity into

the system which lead their assets to soar—to levels north of USD 20 trillion!

Unlike

other heads of government and government agencies, central bankers share a close

bond (some of them address each other on a first-name basis!). They make

contact with each other numerable times a year which helps them furnish a

cordial rapport. This espirit de corps granted central bankers with yet another

tool to combat the economic downturn: If the major central banks of the world

took policy decisions toward the same direction in tandem, there would be a

much severe impact on the world markets [3]. And, it did!

other heads of government and government agencies, central bankers share a close

bond (some of them address each other on a first-name basis!). They make

contact with each other numerable times a year which helps them furnish a

cordial rapport. This espirit de corps granted central bankers with yet another

tool to combat the economic downturn: If the major central banks of the world

took policy decisions toward the same direction in tandem, there would be a

much severe impact on the world markets [3]. And, it did!

Not

only were central bankers coordinating their policy moves, they also conjured up

a mechanism to boost the requisite kind liquidity called ‘Central Bank

Liquidity Swaps’ or merely ‘swap lines’. Through swap lines, central banks in

need of a particular currency could swap it for their own currency. For

example, at the peak of the crisis, the European Central Bank was in desperate

need of dollars to keep their banks afloat. The ECB could exchange their Euros

for Dollars with the Federal Reserve via the swap lines, and meet with the

liquidity requirement in Europe [4].

only were central bankers coordinating their policy moves, they also conjured up

a mechanism to boost the requisite kind liquidity called ‘Central Bank

Liquidity Swaps’ or merely ‘swap lines’. Through swap lines, central banks in

need of a particular currency could swap it for their own currency. For

example, at the peak of the crisis, the European Central Bank was in desperate

need of dollars to keep their banks afloat. The ECB could exchange their Euros

for Dollars with the Federal Reserve via the swap lines, and meet with the

liquidity requirement in Europe [4].

In

addition to fulfilling its ‘lender of the last resort’ operations, central

banks also engineered bailouts of a few firms, most famous of them being the

American International Group and Bear Stearns. Central Banks and the Federal

Reserve in particular took a lot of flak for this move [5]. It hit the moral

wall of dichotomy of using tax-payer money to fund the seven figure bonuses of

executives of firms that brought the economy crashing down into a recession.

addition to fulfilling its ‘lender of the last resort’ operations, central

banks also engineered bailouts of a few firms, most famous of them being the

American International Group and Bear Stearns. Central Banks and the Federal

Reserve in particular took a lot of flak for this move [5]. It hit the moral

wall of dichotomy of using tax-payer money to fund the seven figure bonuses of

executives of firms that brought the economy crashing down into a recession.

Though

some of these policies may seem unfair, it is because of the nerve that central

bankers exhibited at the hour of need—via their bold policymaking—that the

worst economic depression in history remains the one in the 1930’s. They have

shown great character to make unpopular decisions (some decisions against their

own long cherished principles and tradition) even in the face of mounting

adversity to preserve the economic system.

some of these policies may seem unfair, it is because of the nerve that central

bankers exhibited at the hour of need—via their bold policymaking—that the

worst economic depression in history remains the one in the 1930’s. They have

shown great character to make unpopular decisions (some decisions against their

own long cherished principles and tradition) even in the face of mounting

adversity to preserve the economic system.

In

this article, I made an attempt to broach the seemingly ‘reckless’ policies

made to combat the crisis beginning in 2008 without going into much of the

complexities that have evolved to become a part and soul of the financial

system. While I have tried not to take a position with regard to these policies

through the course of this article, I would like to conclude on a note of

commendation. And, even though problems remain in Europe and Japan, and some

rise in China, the new breed of policymakers—who are willing to do whatever it

takes to protect the economy—should inspire confidence of its successful

conclusion.

this article, I made an attempt to broach the seemingly ‘reckless’ policies

made to combat the crisis beginning in 2008 without going into much of the

complexities that have evolved to become a part and soul of the financial

system. While I have tried not to take a position with regard to these policies

through the course of this article, I would like to conclude on a note of

commendation. And, even though problems remain in Europe and Japan, and some

rise in China, the new breed of policymakers—who are willing to do whatever it

takes to protect the economy—should inspire confidence of its successful

conclusion.

NOTES:

1) Nominal

interest rates below zero would mean you would have to pay the borrower for lending out money. Now that

doesn’t make sense, does it?

interest rates below zero would mean you would have to pay the borrower for lending out money. Now that

doesn’t make sense, does it?

2) Monetizing

government debt means intervening in the primary market (the market where

securities are first issued) to buy government bonds. Under QE, the central

bank intervened in the secondary market to purchase bonds. There is one other technicality, as told

by former Fed-chairman Ben Bernanke, cash is not printed immediately, but an

electronic transfer is made to the banks, and cash is printed only when

withdrawals are made at the banks.

government debt means intervening in the primary market (the market where

securities are first issued) to buy government bonds. Under QE, the central

bank intervened in the secondary market to purchase bonds. There is one other technicality, as told

by former Fed-chairman Ben Bernanke, cash is not printed immediately, but an

electronic transfer is made to the banks, and cash is printed only when

withdrawals are made at the banks.

3) The

first of these coordinated moves came on October 8th, 2008.

first of these coordinated moves came on October 8th, 2008.

4) The

swap lines were opened for the first time (with respect to the crisis) on

December 12th 2007: The Fed, The Bank of England, The European

Central Bank, The Swiss National Bank and Canadian Central Bank provided for it

up to $24 billion. This was extended on 18th of

September 2008 by $180 billion and the Bank of Japan was included. Another expansion

by $330 billion came on the 29th of September. And, on the 29th

of October, the central banks of South Korea, Mexico, Brazil and Singapore were

included in this group.

swap lines were opened for the first time (with respect to the crisis) on

December 12th 2007: The Fed, The Bank of England, The European

Central Bank, The Swiss National Bank and Canadian Central Bank provided for it

up to $24 billion. This was extended on 18th of

September 2008 by $180 billion and the Bank of Japan was included. Another expansion

by $330 billion came on the 29th of September. And, on the 29th

of October, the central banks of South Korea, Mexico, Brazil and Singapore were

included in this group.

5) The

Federal Reserve took a lot of heat for bailing out big financial firms and to

certain extent buying up government debt. It was a popular opinion that it was

time that the Fed’s wings be clipped. A lot of stuff went down, but in the end

the Fed soared higher than before.

Federal Reserve took a lot of heat for bailing out big financial firms and to

certain extent buying up government debt. It was a popular opinion that it was

time that the Fed’s wings be clipped. A lot of stuff went down, but in the end

the Fed soared higher than before.

About The Author:

Abhishek Anirudhan is currently a student of economics at Fergusson College, Pune. His interests include international relations, monetary economics and finance.

![Police Reforms – Priority ignored [Republished from Epilogue Press] Police Reforms – Priority ignored [Republished from Epilogue Press]](https://arguendo.co.in/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/41-150x150.jpg)

Leave a Reply