Law, Intersectionality and the Need for Reform

Lawmaking comes to an inherent challenge. Tied to the geographic boundaries of the State it is made for, it is inherently one-size-fits-all in its verbiage, so as to be able to cover all the people that fall in line with its applicability.

This is true in case of the criminal law that penalizes murder with life imprisonment, or intellectual property law that allows for the High Court to revoke a patent on any of the permissible grounds under the law.

And yet, within its geographic boundaries, every State represents diversity in acquired identities, ascribed identities, and experiences that the intersection of identities offers.

The legislature makes the law, the executive implements it, and the judiciary interprets the law to align lawmaking and implementation with justice. In that, the judiciary has the toughest task. Imagine having to take a one-size-fits-all approach to make an impact on the ground where those that are being brought under the law are as different as chalk and cheese. The judiciary has evolved interesting tools of interpretation to create justice-oriented solutions by interpreting the law: beneficial construction to give the wronged one their due, harmonious construction to avoid repugnancy in the letter of the law, and so on.

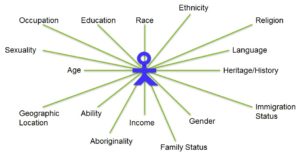

Yet, one wonders why so much time has passed with scant regard being afforded to intersectionality or an intersectional construction of the law. In simple terms, intersectionality accounts for the coming together of multiple identities attribute to create individual, unique and specific experiences comprising privileges and oppressions that are experienced simultaneously. Not acknowledging intersectionality in legislative language is understandable; the sheer volume of specifics is difficult to bridle into words, much less even begin to comprehend given the width of the spectrum. But, in implementation, the gaps can be plugged – and must be plugged to make the law functional and to serve its ends – through judicial interpretation that angles towards intersectionality.

The flaw in our understanding of the law through an intersectional lens, at least in India, is partly because we are still looking at our body of law as our colonial legacy. Most of the legislative instruments, be it our penal code or our contract law, were framed by the British during their rule in India. Save for amended versions, much of the original form is retained. Consequently, we learn to evaluate, interpret and apply the law through a white lens, as opposed to an intersectional, diversity driven lens – and consequently, enforce one-size-fits-all solutions that effectively fail.

Think about it. The Indian Penal Code suggests, in its definition sections, that the word man shall be taken to mean a woman in every reference made to the term. The import of this definition may be dismissed as purely semantic, but look at it in line with the impact of section 377 which is often used to criminalize homosexuality. India has a long history of both embracing homosexuality and gender fluidity as norms and in venerating multiple sexualities and gender identities – and yet, we cling for dear life to the drafts of a white boys club that imposes its notions of acceptable sexual identities. But an intersectional understanding of the Indian ethos will show you that from Ardhanarishwar to Shikhandi, what we turn to as the basis of our antagonism towards the non-binary dimensions of gender, sex, and sexual orientation, actually validates the spectrum and not the concept of gender being binary. A lot of us continue to believe that homosexuality is a western import and a result of a Western invasion of our culture. These explanations are offered from a Hindu perspective, not with the intent to presuppose that Hinduism is the only religion in India but because it has been cited among the loudest arguments to denounce homosexuality.

We are not new to differences in the treatment of survivors and victims by those in charge of the law. A woman can be put on the stand and her character and relationship history discussed and shown as evidence to punch holes in her case. A trans woman belonging to a marginalized caste and a low socio-economic background having faced rape runs the risk of violence, re-victimization, and even criminalization after speaking up. Victims and survivors cannot easily report a case for fear of stigma. Further, the most common discourse we’ve seen in most attempts to throw a case of violence against a woman out of the window is to present it as a false case by painting the reporting victim or survivor as a “person of loose character,” with her sexual history split wide open for the world to see. Women are still seen as property, and their rights are spoken off in the kind of “allowing-language” that Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warned us against. As Kimberle Crenshaw once said, women are put on trial to see if “they are innocent victims asking for it.” Add caste, color, race, and class to the mix and the narrative gets tighter and more stifling for the victim if there are multiple instances of marginalization.

Our approach to implementing and interpreting the law, is then, confined to one-sided perspectives of the law and its implementation. Intersectionality helps us understand the many dimensions of one’s experiences, and how that can effectively affect one’s interactions with the law, the society, and the dynamics of the two. The Rule of Intersectional Construction then can create a more empathetic ear on the benches, and pave the way for greater trust in the security sector – enough to translate into greater reporting, greater accountability on the need to deliver on the reports filed, and finally, translate into an equitable society built on the rock-solid foundation of justice.

About the Author:

Kirthi Jayakumar is an activist, artist, entrepreneur, and writer from Chennai, India. She founded and runs the Red Elephant Foundation, a civilian peacebuilding initiative that works for gender equality through storytelling, advocacy, and digital interventions. She also founded and runs fynePRINT, a feminist e-publishing imprint.

Kirthi is a member of the Youth Working Group for Gender Equality under the UNIANYD. She is the recipient of the US Presidential Services Medal (2012) for her services as a volunteer to Delta Women NGO, and the two-time recipient of the UN Online Volunteer of the Year Award (2012, 2013).

Kirthi is also an author and released her third book, The Doodler of Dimashq, a fictional account of the Syrian War through the eyes of a child bride. Her second book, The Dove’s Lament, made it to the final shortlist for the Muse India Young Writers’ Literary Award.

Leave a Reply