Armed Forces (Assam- Manipur) Special Powers Act: An Overview (Part II)

In May, 2015, after 18 years Tripura became the first State to repeal the controversial Armed Forces Special Powers Act.

But what was/is this Act? And what makes it so controversial?For The Sake Of Argument. presents for you its Armed Forces Special Powers (Assam- Manipur) Act Overview Series in two parts detailing the Act, its objectives and criticisms.

But what was/is this Act? And what makes it so controversial?For The Sake Of Argument. presents for you its Armed Forces Special Powers (Assam- Manipur) Act Overview Series in two parts detailing the Act, its objectives and criticisms.

Read Part I HERE

Section 1: This section

states the name of the Act and the areas to which it extends (Assam, Manipur,

Meghalaya, Nagaland, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram).

states the name of the Act and the areas to which it extends (Assam, Manipur,

Meghalaya, Nagaland, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram).

Section 2: This section

sets out the definition of the Act, but leaves much un-defined. Under part (a)

in the 1972 version, the armed forces were defined as “the military and

Air Force of the Union so operating”. In the 1958 version of the Act the

definition was of the “military forces and the air forces operating as

land forces”. Section 2(b) defines a “disturbed area” as any

area declared as such under Clause 3 (see discussion below). Section 2(c)

states that all other words not defined in the AFSPA have the meanings assigned

to them in the Army Act of 1950.

sets out the definition of the Act, but leaves much un-defined. Under part (a)

in the 1972 version, the armed forces were defined as “the military and

Air Force of the Union so operating”. In the 1958 version of the Act the

definition was of the “military forces and the air forces operating as

land forces”. Section 2(b) defines a “disturbed area” as any

area declared as such under Clause 3 (see discussion below). Section 2(c)

states that all other words not defined in the AFSPA have the meanings assigned

to them in the Army Act of 1950.

Section 3: This section

defines “disturbed area” by stating how an area can be declared

disturbed. It grants the power to declare an area disturbed to the Central

Government and the Governor of the State, but does not describe the

circumstances under which the authority would be justified in making such a

declaration. Rather, the AFSPA only requires that such authority be “of

the opinion that whole or parts of the area are in a dangerous or disturbed

condition such that the use of the Armed Forces in aid of civil powers is

necessary.” The vagueness of this definition was challenged in IndrajitBarua

v. State of Assam[1]

case. The court decided that the lack of precision to the definition of a

disturbed area was not an issue because the government and people of India

understand its meaning. However, since the declaration depends on the

satisfaction of the Government official, the declaration that an area is

disturbed is not subject to judicial review. So in practice, it is only the

government’s understanding which classifies an area as disturbed. There is no

mechanism for the people to challenge this opinion. Strangely, there are acts

which define the term more concretely. In the Disturbed Areas (Special Courts)

Act, 1976, an area may be declared disturbed when “a State Government is

satisfied that (i) there was, or (ii) there is, in any area within a State

extensive disturbance of the public peace and tranquility, by reason of

differences or disputes between members of different religions, racial,

language, or regional groups or castes or communities, it may … declare such

area to be a disturbed area.” The lack of precision in the definition of a

disturbed area under the AFSPA demonstrates that the government is not

interested in putting safeguards on its application of the AFSPA.

defines “disturbed area” by stating how an area can be declared

disturbed. It grants the power to declare an area disturbed to the Central

Government and the Governor of the State, but does not describe the

circumstances under which the authority would be justified in making such a

declaration. Rather, the AFSPA only requires that such authority be “of

the opinion that whole or parts of the area are in a dangerous or disturbed

condition such that the use of the Armed Forces in aid of civil powers is

necessary.” The vagueness of this definition was challenged in IndrajitBarua

v. State of Assam[1]

case. The court decided that the lack of precision to the definition of a

disturbed area was not an issue because the government and people of India

understand its meaning. However, since the declaration depends on the

satisfaction of the Government official, the declaration that an area is

disturbed is not subject to judicial review. So in practice, it is only the

government’s understanding which classifies an area as disturbed. There is no

mechanism for the people to challenge this opinion. Strangely, there are acts

which define the term more concretely. In the Disturbed Areas (Special Courts)

Act, 1976, an area may be declared disturbed when “a State Government is

satisfied that (i) there was, or (ii) there is, in any area within a State

extensive disturbance of the public peace and tranquility, by reason of

differences or disputes between members of different religions, racial,

language, or regional groups or castes or communities, it may … declare such

area to be a disturbed area.” The lack of precision in the definition of a

disturbed area under the AFSPA demonstrates that the government is not

interested in putting safeguards on its application of the AFSPA.

The 1972 amendments to the AFSPA extended the power to declare an area

disturbed to the Central

disturbed to the Central

Section 4: This section

sets out the powers granted to the military stationed in a disturbed area.

These powers are granted to the commissioned officer, warrant officer, or

non-commissioned officer, only a jawan (private) does not have these powers.

The Section allows the armed forces personnel to use force for a variety of

reasons.

sets out the powers granted to the military stationed in a disturbed area.

These powers are granted to the commissioned officer, warrant officer, or

non-commissioned officer, only a jawan (private) does not have these powers.

The Section allows the armed forces personnel to use force for a variety of

reasons.

The army can shoot to kill, under the powers of section 4(a), for the

commission or suspicion of the commission of the following offenses: acting in

contravention of any law or order for the time being in force in the disturbed

area prohibiting the assembly of five or more persons, carrying weapons, or

carrying anything which is capable of being used as a fire-arm or ammunition. To

justify the invocation of this provision, the officer need only be “of the

opinion that it is necessary to do so for the maintenance of public order”

and only give “such due warning as he may consider necessary”.

commission or suspicion of the commission of the following offenses: acting in

contravention of any law or order for the time being in force in the disturbed

area prohibiting the assembly of five or more persons, carrying weapons, or

carrying anything which is capable of being used as a fire-arm or ammunition. To

justify the invocation of this provision, the officer need only be “of the

opinion that it is necessary to do so for the maintenance of public order”

and only give “such due warning as he may consider necessary”.

The army can destroy property under section 4(b) if it is an arms dump,

a fortified position or shelter from where armed attacks are made or are

suspected of being made, if the structure is used as a training camp, or as a

hide-out by armed gangs or absconders.

a fortified position or shelter from where armed attacks are made or are

suspected of being made, if the structure is used as a training camp, or as a

hide-out by armed gangs or absconders.

The army can arrest anyone without a warrant under section 4(c) who has

committed, is suspected of having committed or of being about to commit, a

cognisable offense and use any amount of force “necessary to effect the

arrest”.

committed, is suspected of having committed or of being about to commit, a

cognisable offense and use any amount of force “necessary to effect the

arrest”.

Under section 4(d), the army can enter and search without a warrant to

make an arrest or to recover any property, arms, ammunition or explosives which

are believed to be unlawfully kept on the premises. This section also allows

the use of force necessary for the search.

make an arrest or to recover any property, arms, ammunition or explosives which

are believed to be unlawfully kept on the premises. This section also allows

the use of force necessary for the search.

Section 5: This section

states that after the military has arrested someone under the AFSPA, they must

hand that person over to the nearest police station with the “least

possible delay”. There is no definition in the act of what constitutes the

least possible delay. Some case-law has established that 4 to 5 days is too

long. But since this provision has been interpreted as depending on the

specifics circumstances of each case, there is no precise amount of time after

which the section is violated. The holding of the arrested person, without

review by a magistrate, constitutes arbitrary detention.

states that after the military has arrested someone under the AFSPA, they must

hand that person over to the nearest police station with the “least

possible delay”. There is no definition in the act of what constitutes the

least possible delay. Some case-law has established that 4 to 5 days is too

long. But since this provision has been interpreted as depending on the

specifics circumstances of each case, there is no precise amount of time after

which the section is violated. The holding of the arrested person, without

review by a magistrate, constitutes arbitrary detention.

Section 6: This section

establishes that no legal proceeding can be brought against any member of the

armed forces acting under the AFSPA, without the permission of the Central

Government. This section leaves the victims of the armed forces abuses without

a remedy.

LEGAL ANALYSIS: A CRITICAL OVERVIEW

The

Armed Forces Special Powers Act contravenes both Indian and International law

standards. This was exemplified when India presented its second periodic report

to the United Nations Human Rights Committee in 1991. Members of the UNHRC

asked numerous questions about the validity of the AFSPA, questioning how the

AFSPA could be deemed constitutional under Indian law and how it could be

justified in light of Article 4 of the ICCPR.

Armed Forces Special Powers Act contravenes both Indian and International law

standards. This was exemplified when India presented its second periodic report

to the United Nations Human Rights Committee in 1991. Members of the UNHRC

asked numerous questions about the validity of the AFSPA, questioning how the

AFSPA could be deemed constitutional under Indian law and how it could be

justified in light of Article 4 of the ICCPR.

There are several cases pending before the Indian Supreme Court which

challenge the constitutionality of the AFSPA. Some of these cases have been

pending for over nine years. Since the Delhi High Court found the AFSPA to be

constitutional in the case of IndrajitBarua and the Gauhati High court found

this decision to be binding in People’s Union for Democratic Rights, the only

judicial way to repeal the act is for the Supreme Court to declare the AFSPA

unconstitutional.

challenge the constitutionality of the AFSPA. Some of these cases have been

pending for over nine years. Since the Delhi High Court found the AFSPA to be

constitutional in the case of IndrajitBarua and the Gauhati High court found

this decision to be binding in People’s Union for Democratic Rights, the only

judicial way to repeal the act is for the Supreme Court to declare the AFSPA

unconstitutional.

It is extremely surprising that the Delhi High Court found the AFSPA

constitutional given the wording and application of the AFSPA. The AFSPA is

unconstitutional and should be repealed by the judiciary or the legislature to

end army rule in the North East.

constitutional given the wording and application of the AFSPA. The AFSPA is

unconstitutional and should be repealed by the judiciary or the legislature to

end army rule in the North East.

The Act contravenes the following:

- Violation of Article 21 –

Right to life: Under section

4(a) of the AFSPA, which grants armed forces personnel the power to shoot

to kill, the constitutional right to life is violated. This law is not

fair, just or reasonable because it allows the armed forces to use an

excessive amount of force.

·

Protection against arrest and detention – Article 22: In its

application, the AFSPA does lead to arbitrary detention. If the AFSPA were

defended on the grounds that it is a preventive detention law, it would still

violate Article 22 of the Constitution. Preventive detention laws can allow the

detention of the arrested person for up to three months. Under 22(4) any

detention longer than three months must be reviewed by an Advisory Board.

Moreover, under 22(5) the person must be told the grounds of their arrest.

Under section 4(c) of the AFSPA a person can be arrested by the armed forces

without a warrant and on the mere suspicion that they are going to commit an

offence. The armed forces are not obliged to communicate the grounds for the

arrest. There is also no advisory board in place to review arrests made under

the AFSPA. Since the arrest is without a warrant it violates the preventive

detention sections of article 22.

Protection against arrest and detention – Article 22: In its

application, the AFSPA does lead to arbitrary detention. If the AFSPA were

defended on the grounds that it is a preventive detention law, it would still

violate Article 22 of the Constitution. Preventive detention laws can allow the

detention of the arrested person for up to three months. Under 22(4) any

detention longer than three months must be reviewed by an Advisory Board.

Moreover, under 22(5) the person must be told the grounds of their arrest.

Under section 4(c) of the AFSPA a person can be arrested by the armed forces

without a warrant and on the mere suspicion that they are going to commit an

offence. The armed forces are not obliged to communicate the grounds for the

arrest. There is also no advisory board in place to review arrests made under

the AFSPA. Since the arrest is without a warrant it violates the preventive

detention sections of article 22.

·

The CrPC establishes

the procedure police officers are to follow for arrests, searches and seizures,

a procedure which the army and other para- military are not trained to

follow. The Act contravenes the above.

The CrPC establishes

the procedure police officers are to follow for arrests, searches and seizures,

a procedure which the army and other para- military are not trained to

follow. The Act contravenes the above.

·

The AFSPA grants state of emergency powers without declaring an

emergency as prescribed in the Constitution. The measures taken by the military

outweigh the situation in the North East, notably the power to shoot to kill.

The offences are not clearly defined, since all of the Section 4 offences are

judged subjectively by the military personnel. And the AFSPA is a “special

jurisdiction” provision.

The AFSPA grants state of emergency powers without declaring an

emergency as prescribed in the Constitution. The measures taken by the military

outweigh the situation in the North East, notably the power to shoot to kill.

The offences are not clearly defined, since all of the Section 4 offences are

judged subjectively by the military personnel. And the AFSPA is a “special

jurisdiction” provision.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The Supreme Court has avoided a Constitutional review for over 9 years,

the amount of time the principal case has been pending. The Court is not

displaying any judicial activism on this Act. The LokSabha in the 1958 debate

acknowledged that if the AFSPA were unconstitutional, it would be for the

Supreme Court to determine. The deference of the Delhi High Court to the

legislature in the Indrajit case also demonstrates a lack of judicial

independence.

the amount of time the principal case has been pending. The Court is not

displaying any judicial activism on this Act. The LokSabha in the 1958 debate

acknowledged that if the AFSPA were unconstitutional, it would be for the

Supreme Court to determine. The deference of the Delhi High Court to the

legislature in the Indrajit case also demonstrates a lack of judicial

independence.

|

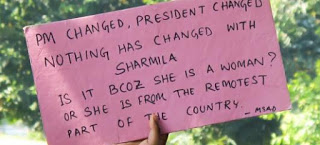

| Irom Sharmila, who is still protesting against the AFSPA for 14 years. |

I would end my article with the view of The UN

Special Rapporteur on the Independence and Impartiality of the Judiciary,

Jurors and Assessors and the Independence of Lawyers, Mr ParamCumaraswamy, who stated

in the 51st Session of the Commission on Human Rights on 10 February 1995, at

the United Nations in Geneva that,

Special Rapporteur on the Independence and Impartiality of the Judiciary,

Jurors and Assessors and the Independence of Lawyers, Mr ParamCumaraswamy, who stated

in the 51st Session of the Commission on Human Rights on 10 February 1995, at

the United Nations in Geneva that,

“The power of judicial review is vital for

the protection of the rule of law.” He also quoted from Mr L M Singhvi’s

1985 report that “the strength of legal institutions is a form of

insurance for the rule of law and for the observance of human rights and

fundamental freedoms and for preventing the denial and miscarriage of

justice.”

the protection of the rule of law.” He also quoted from Mr L M Singhvi’s

1985 report that “the strength of legal institutions is a form of

insurance for the rule of law and for the observance of human rights and

fundamental freedoms and for preventing the denial and miscarriage of

justice.”

About the Author:

Sanya Darakhshan Kishwar is a third year BSc.LLB. student from Central University of South Bihar, Gaya. She is currently interning at For the Sake of Argument.She is passionate about books and loves to read case laws in her free time.

[1]AIR 1983 Delhi 513

![Police Reforms – Priority ignored [Republished from Epilogue Press] Police Reforms – Priority ignored [Republished from Epilogue Press]](https://arguendo.co.in/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/41-150x150.jpg)

Leave a Reply